PERSPECTIVES #3

The cost of the energy transition and social cohesion: an investor’s perspective

Download the full document in PDF formatOne of the usual critiques about the energy transition is its inflationary impact on the cost of electricity. It is true that switching from an energy system focused on large production units and fossil fuels to a system relying on decentralized and renewable energy sources is indeed costly. This is illustrated in the first section.

Whether we are already convinced or not that renewable energy sources -including their impact on system costs- will eventually be the most cost-effective solutions, it is critical to also pay attention to how the population understands and supports this transition, as ultimately consumers bear the costs of the transition. The recent “yellow vest” events in France have been a stark reminder on the need for an energy policy to be not only environmentally sustainable but also affordable to all in order to be socially sustainable.

In this TiLT Perspective #3, we discuss these items, connect them with where we think the best investment opportunities lie and what it means for the investors. with this perspective in mind, we draw 3 conclusions:

- the investment requirement in the whole value chain of the power sector remains massive;

- while energy infrastructure networks or solar and wind farms are well-understood classes of assets, significant value can be found in the other parts of the energy system;

- investing in a socially responsible way is key to the success of the energy transition.

1.The cost of the energy transition

The examples of California and Germany are most often cited to illustrate the impact of energy transition on the cost of electricity. California and Germany are probably most advanced in the rebalancing of their generation mix towards renewable energy sources. Through voluntarist policies and regulations, they both have engaged a shift of their power mix by subsidizing the development of renewables.

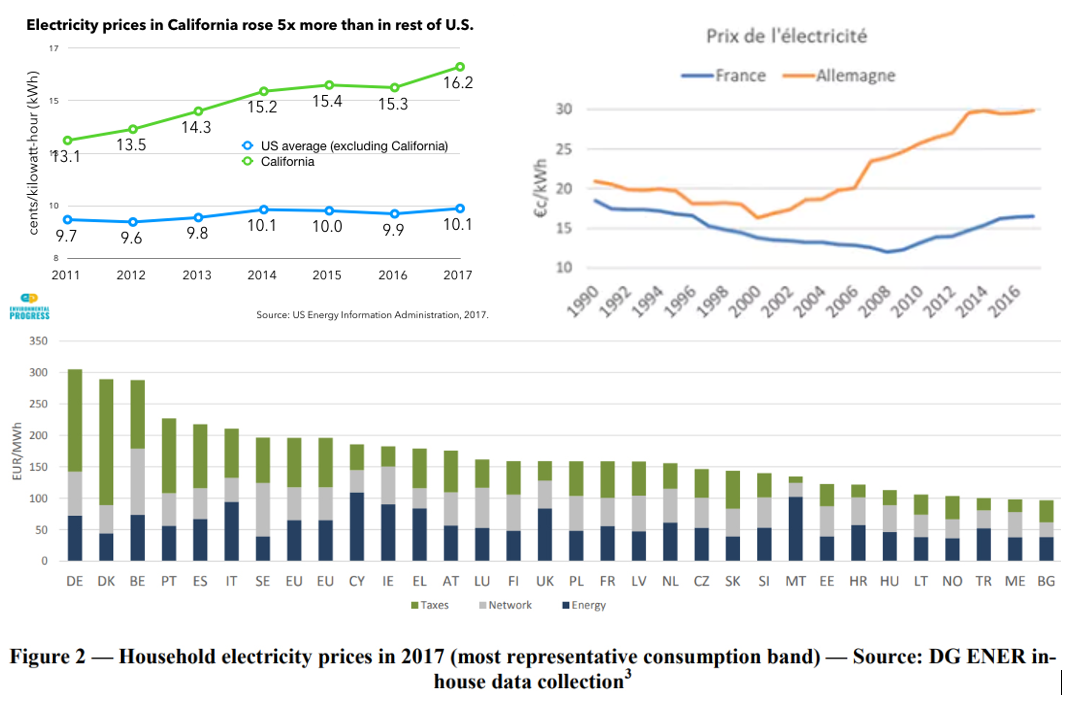

As a result, end-user power prices have increased more in California and Germany than in other areas. Between 2011 and 2017, California’s electricity prices rose five times more than they did in the rest of the USi. In Germany, the higher retail power price compared to other European countries is likewise mainly explained by the increase in taxes and levies of which the “renewables surcharge” for onshore and offshore wind is the highest contributor as illustrated below.

Similarly, in Denmark, the “public service obligation”, which covers subsidies to wind farms and combined heat and power plants, explains the significantly higher power costs than in the rest of Europe.

Beyond the subsidies to cover for the historically higher renewable costs, the transportation and distribution grids require investments for their reinforcement, and otherwise stabilization costs, to ensure the matching of supply and load at all time on the networks, such balance being more difficult to achieve because of the increasing share of scattered and intermittent supply sources. These investments will also weight on the end-user power priceii. In its EnergieWende-Index study, McKinsey estimates that the grid investment costs are lagging, translating into substantial and increasing stabilization costs currently at 13 €/MWhiii. In addition, renewable producers are also paid even when their output is curtailed (this happens when there is an excess of supply compared to what the network can accept) to avoid black-outs.

These evolution towards higher costs must of course be put in regards with the environmental benefits of decarbonizing the supply mix and diversifying away from nuclear energy or imported fossil fuels. This depends on how climate-related damages and the improved security of supply are valued. This value of “externality“ is not the subject of this paper and can be debated at length, but there is consensus to say that it can be expressed in a few % or even tens of % of GDP[iv] (worldwide GDP being close to €90,000bn).

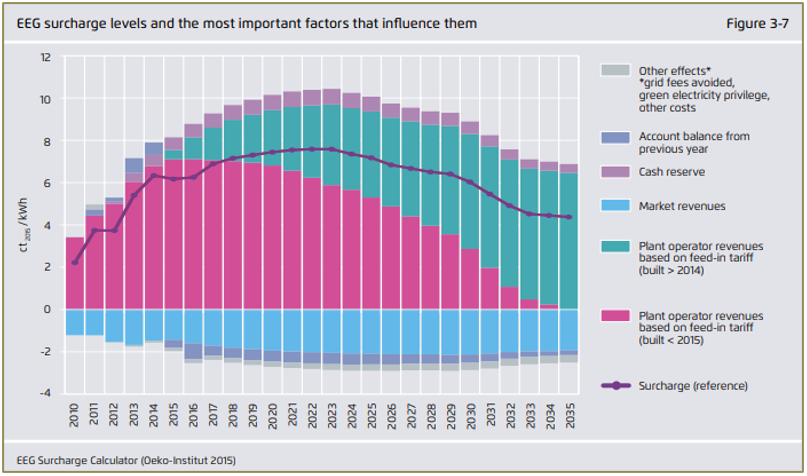

In all likelihood, the current and future investments in renewables will require less and less subsidy, up to a point where these subsidies won’t be needed. In Germany, the cost of all subsidies is expected to peak towards 2023 (see next figure): the first wind farms will exit their feed-in tariff period and the new ones do require less subsidy because of improved cost competitivity vis à vis other generation technologies.

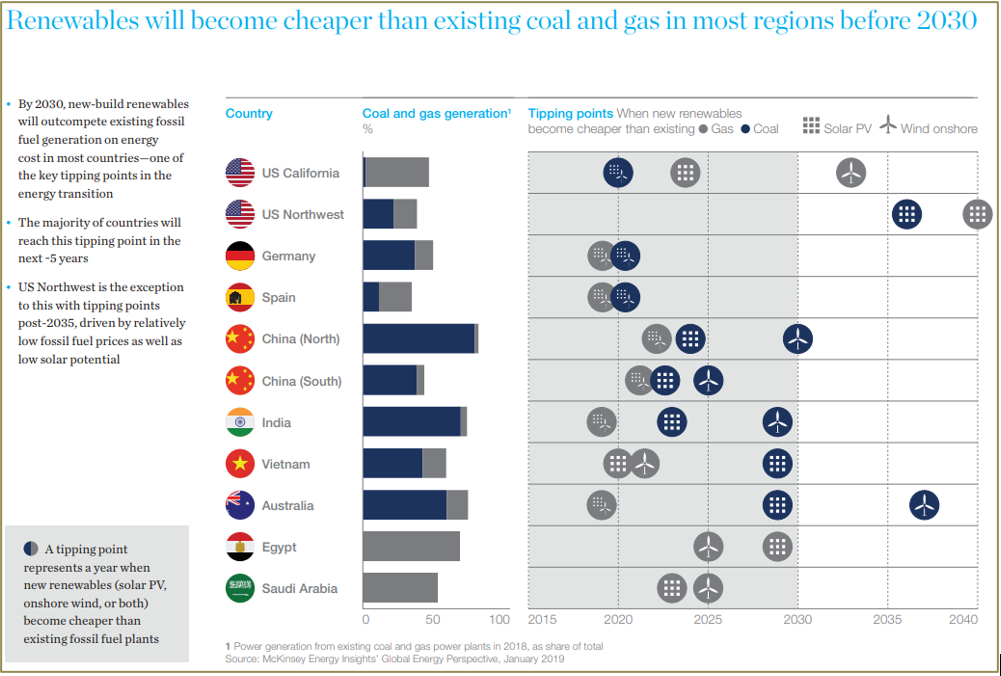

In some part of the world and for some technologies, the cost of renewable power is indeed already lower than conventional power, as illustrated by the McKinsey analysis below which provides the years when new solar and wind units will be cheaper than existing coal and gas-fired generation according to the levelized cost of electricity for each technology. This will not happen at the same time everywhere and for all technologies, because it depends on reaching a scale effect and as it is also a function of local conditions (irradiation and wind resources, tax regime, local O&M costs, etc.), but this will happen before 2025 in most of the regions.

Resulting from the continuous decrease of investment costs and increase of operational performance for the most mature renewable technologies, more and more renewable generation assets are already sanctioned on a quasi-merchant or merchant basis, with minimal or without subsidies, such as onshore wind in Denmark and UK; offshore wind in Germany and The Netherlandsv; solar in Italia, Spain and Portugalvi, or again in Chile or Mexicovii.

2.Energy transition and social cohesion

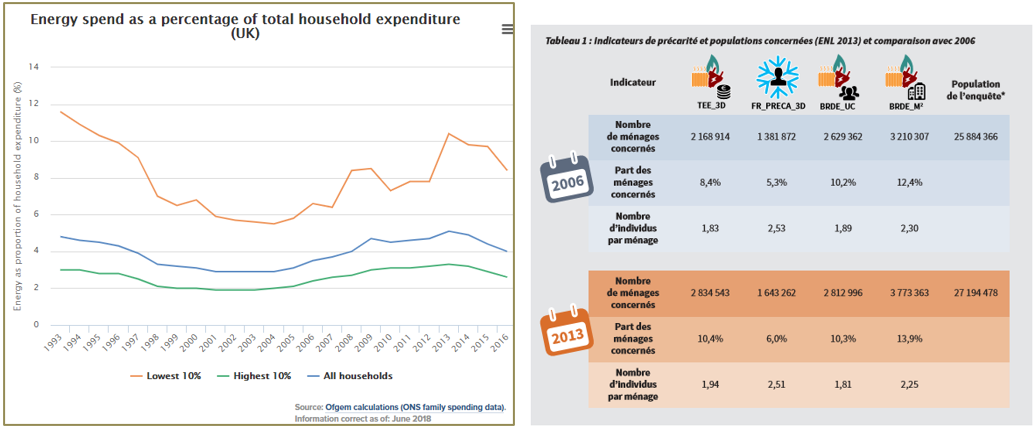

“Affordability” is one the objectives of the European energy policy and forms the energy “trilemma” when associated with “reliability of supply” on one hand and “environmental sustainability” on the other hand. The energy expenditures in dwellings and for transportation represent a significant percentage of available income for Europeans (average of 8% of household income in Franceviii), with significant variations both among European countries and within each country as illustrated below (the right-side picture is taken from ADEME 2013 study “La précarité énergétique à la lumière de l’enquête nationale logement“; it shows that energy poverty has increased over the last years. The first indicator which represents the percentage of households belonging to the last three income deciles that devote more that 10% of their budget to energy expenditures (TEE_3D) has increased roughly 25% between 2006 and 2013). Higher energy costs thus exacerbate the social inequalities as the less wealthy households typically live in more poorly insulated dwellings and make more use of private cars for their socio-economic activities.

The costs associated with the policies and regulations in favor of the energy transition are therefore weighting more on the most vulnerable households, which then may be tempted to oppose the energy transition itself. As an example, the impact of the increase of the CO2 tax in France on the fuel costs sparked the “yellow vest” uprising in France last year. The “yellow vest” movement specifically regroups mainly people who live outside of large cities, typically making daily use of their car, and for whom the increase in energy price is felt as unfair.

The less wealthy part of the population may not afford insulation works on their dwellings, to buy an electric vehicle, to install a more-efficient boiler or to invest in rooftop solar. Third-party financing solutions may help, hence the development of the energy-as-a-service concept, where leasing and other type of equipment financing are offered by energy or equipment providers. Also, a redistribution of some of the CO2 tax proceeds directed towards the poorer households to alleviate their energy bill would also help in both getting support for the energy transition and curbing the social inequalities; research has shown that this is the most efficient way for the population to support energy transition policiesix. Furthermore, this redistribution policy would serve the very purpose of the energy transition: providing financial support to the poorer deciles in order to lower their energy intensity, contributing to reducing emissions which in turn will benefit to the entire society.

In France for instance, targeted policies are available to individual households to support investment in energy efficiency such as insulation; the financial support may be provided in the form of tax credit or rebate, reduced VAT rate, subsidized borrowing rate, direct subsidies. Harmonization of climate policy at national level (the CO2 tax in France does not apply to the aviation sector, which is most benefiting to the wealthiest part of the population) and at supra-national level could also help in getting social support: CO2 from imported goods and services are traditionally not reported in national emissions but are a massive contribution. Many experts advocate for CO2 tax at transnational level, for instance between China and Europex.

As explained in the previous section, some time is needed until the cost of energy fully reflects the cost competitiveness of a post-transition energy supply mix; until then, the burden of implementing the energy transition must be softened as much as possible and especially for the more vulnerable part of the population, such that environmental sustainability and social harmony are reconciled.

3.Investment opportunities and the investor’s role in the energy transition

From its 2017 synthesis of several studies about the European power sector, the European Commission expects average yearly investment of c. €300bnxi. This investment requirement is split into 1/6th for power generation, mainly renewables, 1/6th for the grid and 2/3rd on the demand-side in residential, industrial and tertiary sectors (excluding transport). Recent public statement from the European Investment Bank suggests an increase of this investment requirement assumption to €400bn/yxii. It is interesting to note that investments in the power sector are already higher than in the oil & gas supply sectorxiii.

Based on these numbers, the largest part of the investment opportunity in the energy transition resides in energy efficiency and energy flexibility solutions, ahead of the more mature types of investment in renewable generation units or energy infrastructure networks. Focusing the investments precisely in energy efficiency and energy flexibility does contribute to minimizing the overall cost of the energy transition, and therefore to an easier acceptance by the end-users. This is also a way to avoid increasing, and hopefully to reduce, the social inequalities (and thereby complementing the objectives of all other social impact investment strategies).

The role of the investment community, whether public bodies, corporates or financial investors, is not only to focus its efforts in these domains, but also doing it in a sustainable way. In other words, the way these investments are conducted is as important as the objective of a sustainable and affordable energy system. If an investor wants to create a sustainable success, it can only do so by ensuring financial performance and be sustainable for all stakeholders (end-users, suppliers, employees, public authorities, and the society at large).

This is why we are convinced that not only are Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) matters essential to be profitable in the long run, but they will be increasingly shaping the investment policies of the next decades. This is all the more valid that energy is a basic good. And as past experiences in other sectors such as water and sanitation have demonstrated, investors would be ill-advised to ignore that their license to operate on such basic goods come from the understanding that their value creation comes hand in hand with an improved value proposal to all stakeholders, and especially customers.

[i] http://environmentalprogress.org/big-news/2018/2/12/electricity-prices-rose-three-times-more-in-california-than-in-rest-of-us-in-2017

[ii] Scope Ratings: Corporates Germany’s grid operators face growing multibillion-euro investment challenge (05/03/2019)

[iii] https://energypost.eu/energiewende-enters-a-new-phase-how-is-it-performing/

[iv] https://newclimateeconomy.report/

[v] https://www.greentechmedia.com/articles/read/subsidy-free-onshore-wind-gathers-pace-in-europe#gs.d0qs7d

[vi] https://spain.solarmarketparity.com/market-parity-watch-source/2018/5/1/top-15-merchant-solar-plants

[vii] https://www.solarplaza.com/channels/markets/11720/does-merchant-solar-have-future-latam/

[viii] Bilan énergétique de la France pour 2017, Ministère de la Transition Ecologique et Solidaire

[ix] https://www.novethic.fr/actualite/energie/transition-energetique/isr-rse/quelques-pistes-piochees-a-l-etranger-pour-relancer-la-taxe-carbone-en-france-147262.html?utm_source=AlertesThematique&utm_campaign=16-05-2019&utm_medium=email

[x] http://www.chinawatch.cn/a/201811/20/WS5bf3b639a310c0c381690f5d.html

[xi] European Energy Industry Investment, Study for ITRE Committee, 2017

[xii] https://www.agefi.fr/financements-marches/actualites/video/20190515/nos-investissements-dans-transition-energetique-274824

[xiii] EIA – World Energy Investment 2019